|

| The Acrobats, Gustave Doré (1874) |

Ah, the 19th Century, a time filled with wars, revolutions, and philosophical discoveries. A lot happened during the span of just 100 years, including the birth of countless art movements. Thought colloquially dubbed the Romantic Era, this period had more than just that. The 1800s saw the rise of artists like Monet and Renoir with their Impressionistic styles or JMW Turner and William Blake with Romanticism. It saw the birth of many different movements and the histories of some of the greatest painters of modern times. Of course, there are some that not many people will recognize right away. Romanticism, where the Romantic era gets its namesake, can be loosely defined as subjective, dark, and rooted in horrible tragedies and injustices.

One of the best examples is The Acrobats or The Street Performers by Gustave Doré. It’s one of the most tragic examples of romanticism in the genre. The story is based on an accurate tale of a family of street performers whose child tragically died after an acrobatic fall. Doré had read the account in the newspaper and made a few versions of the piece (Brown). I saw one version in the Denver Museum of Art in 2012 during a school trip and immediately fell in love with it. This version, however, is my favorite. The tarot cards displayed in front of the mother distinctly show an Ace of Spades, which, in layman's terms, symbolizes not only death but the growth of the mind after loss (Arcuri). The owl, chained next to the mother, can symbolize this growth, as owls have historically been symbols of wisdom and knowledge. It could represent the child’s parents going against their better judgment despite the warnings of the tarot reading. The colors Doré used, and the positions he placed the subjects are also symbolic, though in a more religious way. The mother is cradling her son, symbolic of Mary holding the body of Jesus after he was taken down from the cross. She is also dressed in blue and gold, of which Mary is also depicted in most artworks. The father, like Joseph, is pictured away from the scene before him, remorseful at his inability to change what had happened.

|

| Judgment Triptych (1851-53): The Last Judgment, The Plains of Heaven, The Great Day of His Wrath, John Martin (1854) |

On the same subject of religious themes in the genre, I’d like to showcase English painter John Martin’s piece, The Last Judgement (for a better quality version, check out this). This triptych was painted by the famed artist just before he died in 1854. Each painting is imbued with wondrous landscapes and fantastical visuals, a distinctive trait of most Romantic-style paintings. Take a look at the final piece, The Plains of Heaven. The ethereal mountains in the background, the soft flowing meadows, and the pristine waters are meant to elicit feelings of contentment, like it’s saying, “You can finally take a breath.” And it’s no wonder this final piece is so fantastical. The first two portions of the triptych are shrouded in darkness and uncertainty, the threat of Hell and destruction looming over the figures. The rivers of lava and lightning in the background of The Great Day of His Wrath, coupled with the dark clouds and cliffs in The Last Judgement, convey a sense of dread and despair to the viewer. This focus on religion and emotions is almost stereotypical for Romantic paintings.

Attempting to Leave an Impression(ism)

|

| Walk on the Beach, Joaquín Sorolla (1909) |

On the complete opposite end of the spectrum of 19th-century art, we have Impressionism. Originally coined from Claude Monet’s Impression, Sunrise, this painting genre was characterized by muted brush strokes and heavily blended colors. In particular, one of my favorite Impressionist artists, Joaquín Sorolla, depicted two women on a beach in Walk on the Beach. Though painted after the traditional years of the Impressionist period, Sorolla imbues his work with the typical soft colors and muted brush strokes seen in the era. And Walk on the Beach is a masterful description of a typical impressionist painting. The ambiance and perspective of the subjects feel so natural and present that you can almost smell the sea spray coming from the piece. The soft brush strokes and the lack of “harder” lines make this painting, and most impressionism paintings, feel delicate. The wind flowing around their shawls root the viewer in the scene, placing them in the painting with the subjects. These women portrayed were also not “typical” for previous art eras. Starting with the Rococo era, impressionism focused more on the common person or the middle to upper-class person. No longer were works about religion or aristocracy; they were now about the present, of women walking on a beach or the beauty of lilypads on a pond. It was simplistic, to put it bluntly, but sometimes simplistic is all you need for a masterpiece.  |

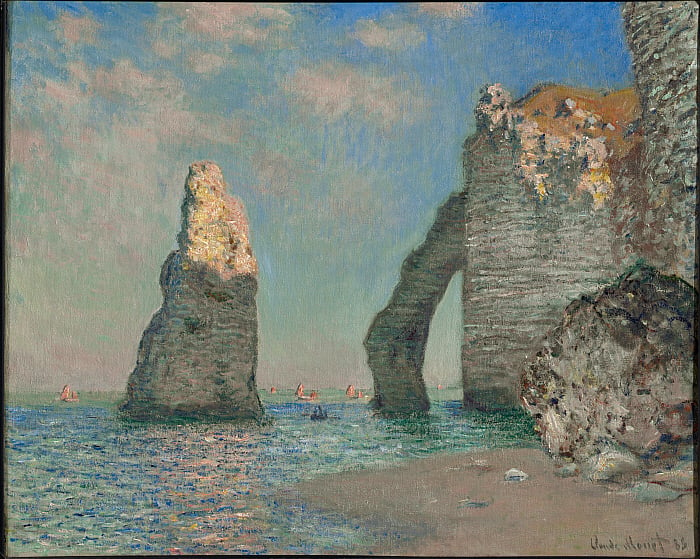

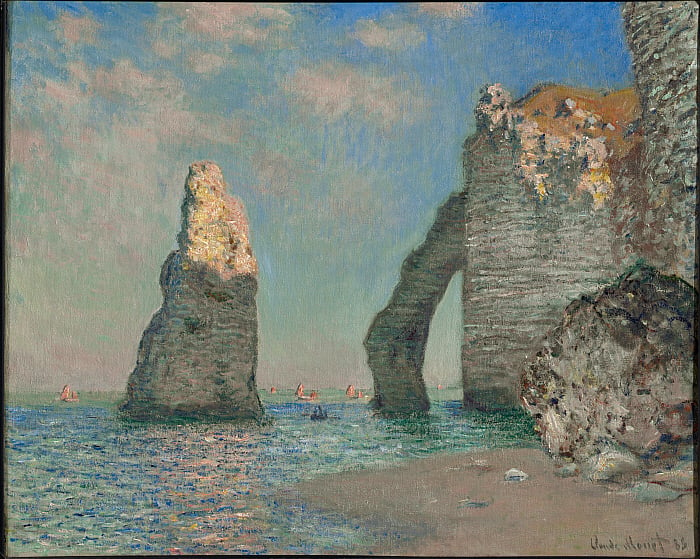

| The Cliff at Éretat after the Storm, Claude Monet (1885) |

To round out impressionism, it's essential to talk about the father of it, Monet. Perhaps the most famous painter of the 1800s (besides maybe van Gogh), Monet painted many pieces throughout his career, but one particular one always stood out to me: The Cliff at Étretat after the Storm. His masterful depiction of light and scene make this piece so comforting. In true impressionistic fashion, the piece looks “unfinished” and sketchy. Monet’s parallels of masterfully blended skies to the blotchy water where every brush stroke is defined is one of the reasons this painting is so unique to me. This not only serves as an example of the serenity of impressionism but as a stark contrast and reminder of just how different genres of painting in the same era can be. The comparison alone between Monet’s Cliff and Doré’s Acrobatics is shocking and surreal.

Works Cited

Arcuri, J. David. “Art of Cartomancy: The Death Card - Ace of Spades.” Art of Cartomancy, 29 Sept. 2019, artofcartomancy.blogspot.com/2019/09/the-death-card-ace-of-spades.html.

Brown, Jen. “Gustave Doré, the Street Performers, 1874.” Narrative Painting, Sept. 2019, narrativepainting.net/gustave-dore-the-street-performers-1874%E2%81%A0/.

Lees, Sarah, et al. Nineteenth-Century European Paintings at the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute. 2012. Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, 2012, pp. 529–33, media.clarkart.edu/1955.528_EuroCat.pdf. Accessed 14 July 2024.

Myrone, Martin. “John Martin’s Last Judgement Triptych: The Apocalyptic Sublime in the Age of Spectacle.” The Art of Sublime, edited by Christine Riding and Nigel Llewellyn, Tate Research Publication, 2013, www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/the-sublime/martin-myrone-john-martins-last-judgement-triptych-the-apocalyptic-sublime-in-the-age-of-r1141419. Accessed 14 July 2024.

ISBN 978-1-84976-387-5.

Stewart, James. “19th Century Art Movements and Their Continuing Influence Today.” Zimmer Stewart, 23 Nov. 2022, www.zimmerstewart.co.uk/post/19th-century-art-movements-and-their-continuing-influence-today. Accessed 13 July 2024.

Hey Damien, what an interesting comparison of styles from the Romantic era. Romanticism as a style is dark, emotional, and vast. Many times, there is a much deeper meaning behind the works to figure out than what is just on the surface. Impressionism as a style uses a similarly softer color pallet like Romanticism but has a lighter and nicer tone. I like the pieces you chose to compare, and they are great depictions of what each style represents. I prefer Romanticisms' aesthetics in this case more than Impressionism because of the darker, more serious tone.

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteWassup Dame Dolla, I found your comparison of styles from the Romantic era really fascinating. Romanticism is dark, emotional, and vast, often with deeper meanings beneath the surface. Impressionism, while using a similar softer color palette, has a lighter and nicer tone. The pieces you chose to compare are great examples of each style. I personally lean towards Romanticism's aesthetics because of its darker, more serious vibe.

ReplyDelete